FEATURES.

Kristi Booth: A Story of Resilience

By Rachael Long

Kristi Booth decided at a young age the world was a hurtful place. And with good reason.

The 43-year old Southeast graduate is a person in recovery from substance use disorder, something she said was amplified by her rheumatoid arthritis. Now, she’s a mother of two daughters, Zoe, 12, and Darci, 7, a university peer ambassador for the Missouri Recovery Network, leads the Friends of Recovery group on campus, organizes the Annual Recovery Walk in September and is an advocate for legislation that would help create resources for people with substance use disorder.

Kristi Booth, 43. Photo by Rachael Long

And while she vowed to her husband she would not work in recovery, Booth finished earning her degree in social work from Southeast in December.

But long before she was an advocate for those with substance use disorder, Booth had a long, dark journey with her own substance use disorder.

She was in and out of jail after “getting busted” when she was making methamphetamine with a former boyfriend. After being released from one of her five stays in jail, Booth returned home to live with her mother. It was then that she began “main lining” the gel in fentanyl pain patches— prescribed for her rheumatoid arthritis— to shoot up. This form of drug use Booth said was “very dangerous” because it had the potential to send a clot to her heart. Because of her medical condition, Booth said she could “get the doctors to give her anything” she wanted.

She overdosed time and again. She recalled one particular instance of overdose in 2003 when Booth said she remembers regaining consciousness to the sound of someone telling her, “You’re going to die if you keep doing this.”

It was then Booth decided she didn’t want to die.

The next day, she called Family Counseling Center and began taking the first steps to recovery.

It was in a 12-step program where Booth met her now husband, who she described as “a very generous, loving man” who was “completely different than any other man” in her life.

After nearly nine years without drugs, Booth said she had a flare up of arthritis which caused her to have to take prescription pain medication. Because she was part of an abstinence-based recovery program, Booth said she didn’t want to tell anyone about what she was going through.

She experienced a recurrence with substance use disorder. Thanks to a push from her husband, Booth called the Gibson Recovery Center.

Her new date which marks the time since she last used is Nov. 23, 2013.

But Booth lived a lifetime of darkness before she would arrive at her new date in 2013. During the years when her substance use disorder controlled her life, she said her drug of choice was “everything and more.”

It all started when she took her first drink of alcohol at age 5. She was repeatedly molested by her grandfather, and Booth said she remembered how the alcohol was the only thing that made her feel good.

“I didn’t know how to cope with it,” Booth said.

She had even more to contend with when, in her early adolescent years, she was forced to become a parent in her mother’s absence.

She said her mother, then addicted to prescription medication, was “knocked out” for most of Booth’s childhood, spent in Cape Girardeau. Cooking, cleaning and getting herself to school each day became her responsibilities.

In her high school years, Booth said she was raped by “multiple people.” She was even in a coma after an incident where she tried to take her own life. A few weeks after having her stomach pumped from that incident, Booth returned to school where she said she tried to lay low and avoid her rapist in the halls.

Eventually, Booth said she took a safety razor to her wrists. She just wanted the pain to stop.

That’s when her mother offered another dark alternative to her pain. She handed Booth a bottle of pills.

“‘If you really want to die, you can take this bottle of pills and go to sleep and never wake up,’” Booth recounted her mother having said to her.

She said she didn’t want to die, she just wanted help.

Her mother took her to the hospital, where Booth told a nurse what her mother had offered her. It was then Booth was taken from her mother’s custody “because, quite clearly, she was unfit” to raise her any longer.

She went into the foster system where she stayed until she aged out at 17. Her social worker had been helping her get disability money for her rheumatoid arthritis, a condition she’d had since she was a baby. That money, along with the child support her father paid to the state, allowed Booth to get her first apartment by herself.

“As soon as I got out, that’s when the party began,” Booth said.

It was then Booth said she began using illicit drugs. Alcohol, marijuana and LSD were the drugs she said she used most often.

It was after she began touring with the Grateful Dead and hitchhiking across the country that Booth said she found methamphetamine.

“That’s when it wasn’t fun anymore,” Booth said.

Booth said she weighed 89 pounds the last time she was arrested for methamphetamine, back in 2002.

She said methamphetamine, which she began using in1994, led her to meet her then boyfriend— the one who helped get her in trouble with the law— the man who would come to abuse her mentally, physically and psychologically.

It wasn’t until Booth became pregnant by her abusive boyfriend that she realized she could not control her drug usage. Until her pregnancy, she said she had been on probation, in and out of treatment centers and jails.

Despite her best efforts, she couldn’t stop using.

“I realized this was something other than me just doing what I wanted,” Booth said. “This was something I had to do.”

Her baby, named Noah, lived for only two weeks. Booth said he died from complications of her drug abuse.

It was the first time in her life that Booth said she had ever felt a true, unconditional love. Having Noah gave her hope in an otherwise dark time.

Booth stayed with her boyfriend despite many instances of domestic violence. Booth said they both spent time behind bars for a drug bust, her in jail and him in a federal prison in Kansas.

During her time in jail, Booth said she met a woman who was getting ready to leave prison who told her about God. And although Booth’s father was a pastor and she’d known God in some sense, she never had a meaningful relationship with him.

“I told her that I didn’t ask for God to help me when I was doing what I wanted to do, I’m not going to ask him to help me when I’m in trouble,” Booth said.

But Booth said the woman “had this light about her” and it made her reconsider.

“I got down on my knees and I just said, ‘God, help me,’” Booth said. “I believe that was the moment the door was opened.”

Today, Booth said she tries to be honest about her life experience with her children whom she said are genetically predisposed to have substance use disorder.

Kristi Booth pictured with her two daughters, Zoe (left) and Darci (right). Photo by Rachael Long

Her daughter Zoe, Booth said, has even thanked her for her honesty and says her friends don’t have the same understanding about the world that she does.

That different perspective and understanding of the world is something Booth hopes more people possess after hearing her story.

“People with substance use disorders are just people,” Booth said. “We just have a neurological disorder that’s got us not living right, not making good decisions. Whenever we have the substance in our system we lose the power of choice.”

Booth said substance use disorder is a mental health issue, and she hopes to change the stigma surrounding how people understand addiction.

Despite the darkness of her past, Booth has found a way to use her story to help others, something she always wanted to do with her life.

“All that crap I went through...I know that there was a reason,” Booth said. “God loves me and God’s going to use me.”

Booth credits much of her recovery to her faith in God. She said she called on him many times and he “showed up and showed out.”

Booth said she isn’t sure there are many things that could have stopped her from using drugs because of how much trauma she faced as a child. But after a lifetime of consequences from using, she knows how important prevention is in the fight against the opioid epidemic.

Prevention, she said, needs to be the first step.

In her own life, Booth said she continues to take measures of prevention. She has had to have surgeries which require her to use pain medication. But Booth said she now has people in place to support her. She doesn’t hold the pain medication and has sponsors to help hold her accountable.

She also acknowledged the role of big pharmaceutical companies in her journey with substance use disorder, claiming they encouraged physicians to over-prescribe medication to make a profit without worrying about the lives affected.

Booth said those who struggle with substance use disorder need money for recovery, not just treatment. After receiving treatment, she said, they are put right back into the environments in which they developed their disorders. Recovery in those cases can be impossible, Booth said.

The very thing which nearly took her life time and again is now at the heart of her campaign for justice and recovery.

“It was worth it, it really was. If I can help one person, it was worth it,” Booth said.

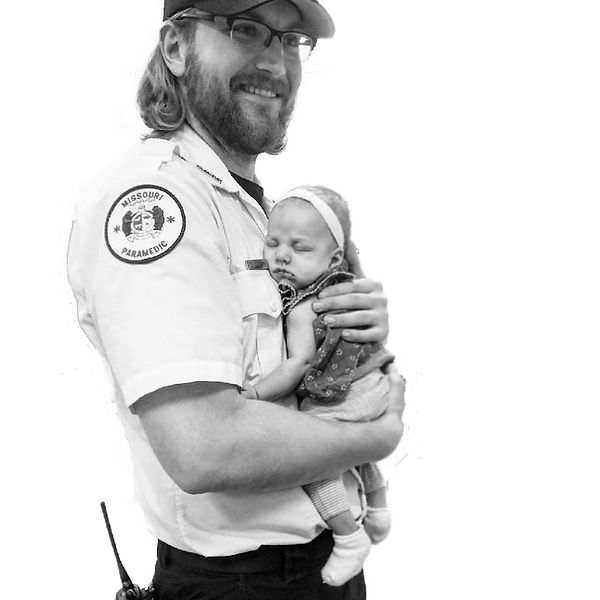

David Ludolph: A Paramedic's Personal Connection

By Matthew Dollard

David Ludolph was working the night his brother died.

“I didn’t [respond to the call] thank God,” Ludolph said. “Someone else I was working with did.”

Ludolph is a paramedic for Cape County Private Ambulance and a former Southeast student. He said it was by chance he wasn’t sent to treat his brother.

“I recognized where it was,” he said. “I was assuming, and kind of freaking out, because really, it was supposed to be my call, and they accidentally messed up the rotation.”

He said his younger brother, Wade Ludolph, had been alienating himself in the months leading up to his fatal overdose in October 2017.

“I had suspected stuff was going on with him like that, like he was probably doing something again,” he said. “I probably hadn’t seen him in six months. Tried to, but hadn’t. Before going to bed it was running through my mind, like, ‘What if I end up having to run [a call] on my little brother.’”

David was with another patient when he received word of Wade’s death. David’s co-worker, who responded to the call, administered Narcan, a drug that reverses the effects of overdose. But too much time had passed.

“He was way past help, and they still tried to help him,” David said. “I saw him in the hospital, he was blue.”

David said his brother’s opioid use was a result of too-easily accessible prescription drugs, and possession charges that lingered, setting him up for failure.

“He got arrested and got caught with a bunch of different pills, bunch of heroin, went to jail, got out, was clean, was doing great, really really good,” he said.

But Wade’s felony charge made finding a meaningful job difficult and depression crept back in, with drug use close behind.

“You’re trying to shield how you feel and it builds up and builds up, so you keep doing the heroin to not deal with it,” David said. “So I think it prolongs the reasons why you’re feeling depressed. They do it to be numb and to forget.”

He said the charges associated with possession of opioids are doing more harm than good.

“There’s a difference between having a brick of heroin to sell to people, and being found with a little bit. The only person it's really affecting is the person doing it, and they need help, they don't need punishment. It makes it even harder for them to get out of where they’re at.”

Even without a car, Wade was able to access heroin and other substances in Cape Girardeau.

“I think it’s a really really hush, hush thing,” he said. “I think it’s ‘Well, this guy’s done heroin with me a couple times, I’ll see if he wants to buy some now.’”

But Wade’s addiction began much more traditionally.

“Really I don’t think heroin is where it starts; I think access to prescription opioids is where it starts,” he said. “I almost guarantee you he tried prescription opioids before heroin. It’s just the access to it; it’s crazy easy. The first time someone does an opioid it was prescribed to them.”

David truly believes that he and his family did all that they could to be there for Wade.

“He had all kinds of people trying to help him, all kinds of people, and I think it really comes down to the availability of help, I guess, and how much they want help,” he said.

Treating Opioid Overdose

Ludolph has been working as a paramedic for four years. He said he and his co-workers encounter fatal opioid overdose once a week on average.

For that reason, Narcan has become an indispensable resource. Ludolph said he ensures his ambulance is stocked with enough Narcan to treat several people each shift.

It can be administered intravenously or nasally, Ludolph said, depending on the condition of a patient’s veins.

“If they’re shooting up, their veins are probably terrible,” Ludolph said. “If their veins are in good shape, I’ll start it intravenously.”

Ludolph said in Cape Girardeau, calls related to opioids may mean responding to known users or to older adults having adverse effects to a new medication.

Heroin users, he said, are very rarely over 30. In Missouri, in 2016, 29 percent of heroin overdose deaths were between 25 and 34 years old.

Ludolph has four years under his belt as a paramedic, and said knowing how to avoid combativeness is a key to treating overdose.

Before treating an unresponsive patient with Narcan, he said he tries to rule out other possibilities, especially if illicit drug use is not obvious, but the signs are almost always the same.

“Pin-point eyeballs, they’re not reactive or unconscious, it’s probably some kind of opioid,” Ludolph said. “Low heart rate, low blood pressure, barely breathing; that’s probably what it is.”

He said administering Narcan is best done slowly and carefully because “slamming it” can cause a state of immediate withdrawal in opioid dependent patients, causing seizures and vomiting.

He begins with .5mg and works up to 2mg, while monitoring vital signs. If the patient shows no sign of improvement, another 2 mg is pushed slowly.

“Generally after that you can kind of tell that they are probably gone,” he said.

But when the treatment is effective, he must remain alert.

He said patients often grow combative after Narcan is administered, because the substance has effectively taken away their high. Working from inside his ambulance is where he feels most secure, and getting the patient to the hospital is a priority, but it often takes some convincing.

“Everyone responds differently to Narcan,” he said. “Some people, right then and there, start talking to you, some people are still confused for awhile. Another factor can be how close they were to being dead.”

He said users almost always lie about their drug use, even after being revived from overdose.

“People with addiction lie, and that’s just part of the disease, to protect the addiction basically,” he said.

He said his uniform, to a confused overdose survivor, resembles law enforcement, and makes it difficult to build trust with the patient.

“That’s another reason why we try to get them to the hospital,” he said. “Hospitals have more time and resources to gain their trust and treat them better.”

It is not uncommon to have to restrain overdose survivors, and if the patient is a known user, who is prone to violence, a police officer can sometimes ride along in the ambulance to the hospital.

He said when he began work as a paramedic, emotion and nervousness played a role in his treatment of patients.

“Now I’ve just done it for so long, I know that staying calm and the disconnect is important and you kind of push off how you feel until after the call,” he said. “Then it all kind of rushes in and you’re, like ‘OK, now you’re allowed to feel.’ Because to do your job, if you do it emotionally, you’re going to screw up, or you might forget to do something, because it kind of clouds your brain.”

He said clarity is imperative because of the risks associated with the job, including extremely potent synthetic drugs that can cause harm upon contact.

On Narcan, David said although it is saving lives, he believes it is, in a sense, fueling the fire of addiction.

“He was way past help, and they still tried to help him. I saw him in the hospital, he was blue.”

~ David Ludolph

"Really I don’t think heroin is where it starts; I think access to prescription opioids is where it starts.”

~ David Ludolph

“People with addiction lie, and that’s just part of the disease, to protect the addiction basically."

~ David Ludolph

David Ludolph. Submitted photo.

Kelly Gant: One Year Later

By Matthew Dollard

Kelly Gant studies athletic training, rides a motorcycle and is about to finish her freshman year at Southeast. She is also a year into recovery from substance abuse.

She found a recovery program she could get behind, and relationships that yield genuine happiness, in place of the artificial kind.

After graduating from high school a year earlier — she said because the pills she was taking made her hate the place — Gant’s substance use grew heavier.

She had no plans, at that time, to attend college. She said her goals had been changed to meet her behavior.

At 16, growing up in West County, a suburb of St. Louis, Gant said she was using xanax casually. The doses grew suddenly stronger and she became dependent on them.

After overdosing on what she believed were pharmaceutical pills, tests at the hospital revealed no xanax. Gant had overdosed on fentanyl.

She was in disbelief at first and confronted the source of the pills. She said the guy was older, with ziplock bags full of hundreds — if not thousands— of pills, he sold to high school kids.

“I remember asking him ‘How are you getting these?’” Gant said. “He kind of laughed at me and said, ‘I’m making them.’”

Gant said the dealer had acquired a high-end pill press on the dark web, and used it to create identical clones of xanax and other prescription medications, with fentanyl as the primary ingredient.

“There were white ladders, they were 1 mg, and probably had no xanax in them; the yellow school busses were 2 mgs and he’d put, like, 20 percent xanax powder in them, and the rest would be fentanyl. And then there were the green monsters,” Gant said.

She said the counterfeits were indiscernible from the real thing in appearance.

“It was something totally different, but most kids wouldn’t even know,” Gant said. “Normal xanax you could take like 3 or 4 bars and you’re not gonna die or anything, but you take 3 or 4 of these bars that have fentanyl in them, which is like synthetic heroin, you can get really messed up.”

The counterfeit fentanyl pills became synonymous with physical dependence.

“He’d sell to a kid, give them a deal on a couple, so they’d take one, take one the next day and want one the next day,” she said. “It definitely did it for everyone, and all these kids thought they were just addicted to xanax.”

Gant became friends with the dealer, and said she was fascinated by the illegal press operation he maintained with his knowledge of the dark web.

“I couldn’t really complain because It was better than xanax, it was stronger,” Gant said. “[The dealer] said, ‘This is better, you’re getting more than your money's worth so you should be thanking me that you’re getting something better.’”

Three other people had been hospitalized for overdose on his fentanyl pills, Gant said, before he began feeling guilty. When two people died from the drugs he’d sold them, he said he’d stop.

But the profit margin he’d set up selling cheap fentanyl as expensive pharmaceuticals was its own addiction.

“He was making over 100K in less than a year,” she said. “He was like, ‘Well they’re gonna get it from someone, I'd rather them get it from me.”

Gant said the dealer was never brought to light for his crimes.

Her own criminal record, Gant said, is clean considering the number of charges brought against her when she was using pills.

“That would not happen to anyone else unless they had money to get them out of it,” Gant said.

She joined an outpatient treatment program, in lieu of a court sentencing, but said she wasn’t committed. It took a friend, and former user’s urgence to try a young person’s anonymous recovery group, in St. Louis, for her to realize she wanted to make a change.

Weekend young person’s meetings continue to be a source of strength for her, and the relationships she said, are helping her to better herself. She sought for a similar recovery group demographic in Cape Girardeau, but was unsuccessful.

She said older people in recovery generally do give the best advice, but that they’re sometimes too far removed from their addiction to relate.

Zach Norris: A Recovered Man

By Kara Hartnett

“I ended up on my knees in the rain stopping traffic and I didn’t know what else to do."

~ Zach Norris

“I felt my addiction break."

~ Zach Norris

"I couldn’t just do a little bit of any drug. I had to do it as much as humanly possible.”

~ Zach Norris

Throughout his life, Zach Norris struggled to find stability.

The last time Norris was hospitalized for overdosing, he was found in the middle of a street, blocking traffic, on his knees.

He had spent the week not sleeping, selling meth. As he was about to rest for the first time in days, a man came over with a stash of ecstacy — Norris obliged.

They sat down, packaging the paraphernalia. Norris said they began taking tears and enjoying themselves.

Norris didn’t have a particular drug of choice, he just used whatever he could get his hands on.

Shackled by paranoia from his elevated drug consumption and the ringing of sirens from the nearby hospital, Norris began to flee from his home to escape what he thought to be an impending police raid.

He dashed from his home barefoot, jumped into his car and slammed it into gear.

As the sirens grew louder in his head, Norris kept checking his rearview mirror for a hint of the red and blue lights on his tail. He didn’t see anything.

The police weren’t chasing him, he just didn’t know it.

Next thing Norris knew, he had crashed his car into an apartment complex. The episode did not end, however, as he fled the scene on foot despite his injuries from the crash.

He was desperate, all he knew is he needed to escape the police.

The police that weren’t chasing him.

“I ended up on my knees in the rain stopping traffic and I didn’t know what else to do,” Norris said.

Instead, he was greeted by real sirens. An ambulance drove up to him, the paramedics found him on his knees and escorted him to the local hospital where he spent five days getting sober.

Those five days, Norris said, he just tried to piece his mind back together. From a rapid heart rate to hallucinations, Norris would “smoke” from his finger thinking it was a cigarette. He said during that time, he experienced every withdrawal symptom imaginable.

“Once you’re at that level, it’s hard to put it all back together,” Norris said.

In his brokenness, Norris began merging together the pieces of his life.

It took seven car crashes, 10 rehabilitation centers and several missteps along his journey for Norris to find his balance.

After 12 years of being addicted to every drug in the book, Norris found solitude at Teen Challenge, an all-men inpatient rehabilitation center, where he spent 14 months as a student, and years following as an intern.

Norris said his time as Teen Challenge marked a turning point, a time of higher standards, responsibility and hope.

Much of his recovery, Norris attributes to spirituality.

“I guess it connected me to something bigger than myself,” Norris said. “Maybe it’s connected me to something that has told me I can do anything. Because before I couldn’t do anything at all, and I proved it over and over again.”

Teen Challenge, a faith-based organization, allowed his spiritual connection to ferment and lift him from the darkness of his addiction.

“I had one church service where I really felt something happened, a spiritual thing, where I felt my addiction break,” Norris said.

Other than that, Norris said he took his recovery day-by-day. He would absorb what he was learning during his time at Teen Challenge, and set precedents and goals he met every single day. He said sometimes it was hard, but he knew in order to adequately recover he could never lower his standard.

“Sometimes it’s an emotional thing, sometimes it’s mental, but other times its using those principles that you learned and being able to apply those into your life, even through more difficult times,” Norris said.

In 2013, Norris left Teen Challenge a changed man, and started to attend a bible college in Springfield.

Not long after, he relapsed.

He was quick to return to Teen Challenge, where he went through a restoration program that supplied him with the extra assistance he needed to stop using again.

Since his restoration in 2014, Norris has been sober and climbed through the ranks in the Teen Challenge administration during recovery.

He started off as an intern and general staff member. Through hardwork and dedication Norris became the intake director, then the academic dean, then the medical director.

Today, Norris is the program director at the Adult and Teen Challenge Mid-America induction center.

The career he found in Teen Challenge motivated him through his recovery, and set a precedent for himself to be someone students going through the program could rely on and look up to.

“I started seeing people depend on me,” Norris said. “If I wasn’t there to wake the guys up in the morning, I saw how that could affect their routine and cause a guy to get upset and leave. When they leave, they could die ... it happens all the time.”

Being a good role model for his students is particularly important to Norris, because idolizing the wrong role-models is what began his long-time addiction.

At 9-years-old Norris said rock n’ roll had a grasp on his soul, and Jim Morrison’s famous quote “the road of excess leads to the power of wisdom” intrigued him.

“I had church people that raised me, and did good in school,” Norris said. “I think maybe what got me mixed up from an early age was I had a skewed view of what a hero was.”

With inspiration from his idols, Norris began filling water bottles with vodka and taking them to school when he was 13 years old, as well as smoking marijuana.

The behavior soon developed into something much worse.

“Everything I ever did was 100 times greater than it needed to be,” Norris said. “I couldn’t just do a little bit of any drug. I had to do it as much as humanly possible.”

He encountered his first rehabilitation experience at age 15. For one year, he fought his addiction for the first time. After that year, Norris returned to the drugs that put him there.

Throughout high school, he said he was just trying to have fun.

“I thought having fun always had to include extras, like I could never just be satisfied with myself or my current circumstance,” Norris said.

Between the music festivals and getting high with his friends, Norris’ addiction grew stronger when he was introduced to synthetics. From there he started using meth, heroin and pain pills.

“I couldn’t stop myself, and I would do absolutely anything to keep going,” Norris said.

Eventually, he was sent to New York to detox and go through a heroin recovery program. The trip, however, did more harm than good. In New York at the time, heroin was everywhere — and cheap.

“At New York, I would fall apart at a sober house. I didn’t have friends or family or anybody there,” Norris said. “I was literally a homeless drug addict. I would be detoxing with pneumonia at the same time, and just constantly falling apart.”

Living in the streets of New York, Norris knew little about the future that was in store for him.

“To have what I have now, and have an entire program under my view, there’s a lot of people that depend on me, and it really helps me keep my standard,” Norris said.

Now, he’s living a life he could only dream of.

“My life now is pretty cool, I am married and have a 12-year-old daughter from before, with a baby on the way,” Norris said. “I have a house, and a couple dogs and a nice vehicle and a nice wife.”

Even four years into recovery, Norris still faces challenges. He has to dispose of needles and other drugs quite frequently, staring his past addiction right in the eyes. He said that although it bothers him, dealing with little things like needles over time has really made a difference.

He’s dedicated his life to helping other suffering from addiction, and keep a high standard for himself so others know they, too, can recover.

“There’s hope, you’re never counted out. No matter how dark it is, or how deep the hole, every passing minute is a chance to turn it all around,” Norris said. “Everything can change in an instant. It has to start with a brokenness, that there's a better life out there and that he has to get it.“

Understanding Addiction from Afar

By Rachael Long

*Editor’s note: The source’s name for this story has been changed due to the sensitivity of this report.

Southeast senior Jane Smith is studying political science and social work and spent most of her adolescent life around people abusing or misusing opioids.

While she never used drugs herself, Smith grew up in an environment where she said it was common to see her peers actively use drugs. She said she has known upwards of 10 people from high school who have died of mostly heroin-related drug overdoses.

A native to St. Charles, Missouri, Smith is the daughter of a social worker and a lawyer and said she grew up comfortably. Despite her family’s financial stability, Smith said her area in St. Charles was made up of diverse demographics, and the drug problem drew no lines.

But substance use disorder hits closer to home for Smith than just at the peer level. Once a prominent lawyer in the St. Charles area, her grandfather retired several years ago and has since developed a new substance use disorder, Smith said. Long before she was “even a thought,” Smith said her grandfather abused substances. But where his vice used to be alcoholism, now his drug of choice is prescription pain medication.

Smith said her grandfather, now 65, stopped drinking when she was somewhere between the ages of 12 and 13. Because he was a former alcoholic, Smith said he had a higher tolerance for other substances and was therefore much more susceptible to substance use disorder.

In the last five years, her grandfather has overdosed twice on painkillers.

When he was a young man, Smith said her grandfather had a back injury. The pain from that injury is something he still lives with today, and Smith said her grandmother was picking up more than $500 worth of painkillers for him each week.

“He’s an addict, and he was actively knowing he was abusing pain pills,” Smith said. “My mom was like, ‘Hey, this is ridiculous, you’re gonna kill yourself.’”

Since then, her mother has taken control of her grandfather’s situation and switched him from a local doctor in St. Charles to Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis. Smith said they have been weaning her grandfather off painkillers, and “his health has only gotten better.”

Smith attributes much of her grandfather’s addiction to painkillers to the overprescribing habits of his former doctor.

“His tolerance is just too high but he didn’t have a doctor who said, ‘Hey, listen, I know you’re in a lot of pain, but there’s no reason you need to be on this many painkillers. It’s a concerning amount,’” Smith said. “His doctor never did that, just kept prescribing him.”

Watching her grandfather battle with his opioid addiction was not as emotionally traumatic for Smith as it may seem. She said both of her parents’ careers were in social work during her formative years, so drugs were always a “casual topic” in her family.

She said her parents’ honesty and openness about drugs, a traditionally taboo topic, helped her keep from being judgemental toward her peers who were “actively using” substances. It also gave her the wisdom to know when to stay out of dangerous situations.

“My parents were … super understanding, never judgemental, but because of what we were surrounded by, they set a very clear expectation,” Smith said. “It was kinda like, you know, ‘We love you no matter what and we know that not all drugs are bad, but we don’t use them in this house because it can very easily become a problem.’”

Smith said her genetic predisposition for addiction increased fourfold her chances of becoming a person with substance disorder. That alone was enough to scare her out of ever trying them.

Being a family member of someone dealing with substance use disorder, Smith said, can be highly frustrating, noting drug addicts are by nature “kind of selfish...even if they’re not trying to be malicious.”

That selfishness is what she said makes it hard to be a friend or family member to a person with an addiction.

“Once somebody is an addict for so long, no matter how much you love them, it’s just frustrating. Addiction is annoying,” Smith said.

Understanding the biology behind her grandfather’s substance use disorder is the way Smith said she copes with that frustration.

Because her grandfather began taking painkillers for an injury in his 30s and still takes them more than three decades later, Smith said she knows his tolerance for pain medication is simply much higher than that of a non-addicted person.

People with substance use disorder, she added, respond to other drugs better than any other person. Smith noted her grandfather was essentially predisposed to become an addict after his alcoholism.

“Abstinence is, in a lot of ways, a real luxury,” Smith said.

Smith emphasized the point that the opioid epidemic is not a new problem, but instead it’s just now receiving adequate attention in society.

“There have been drug epidemics in this country forever. Like in the 80s and 90s, black people were dying on the streets left and right due to a crack epidemic,” Smith said. “When that crack epidemic happened, we created the ‘War on Drugs,’ and whenever white kids started getting addicted to heroin, all of a sudden we had an opioid crisis and everyone feels bad for drug addicts.”

As someone headed into a career field with intent to use her educational background in both political science and social work, Smith knows how important policy is in addressing the epidemic from a historical standpoint.

“Specifically when it comes to drug policy, we measure ‘poor people drugs’ differently than we measure ‘rich people drugs,’” Smith said.

And while developing ways to help combat the epidemic are important, the issue itself is not new, and Smith said it shouldn’t be treated as such.

“It’s kind of disrespectful to people who have been living in north St. Louis city who have been dying for 70 years from drug addiction and then all of a sudden us kids in St. Charles city start getting into drugs and within five years we have, you know, drug court and policies and implementation and drug classes and classes that they never got over there,” Smith said.

One way Smith said the epidemic can be combated is through more open conversations in homes about drugs, even though it may be an uncomfortable subject.

She noted substance use disorder is a preventable disease, but Smith said “it’s not preventable for everyone.” While some children grow up in households where drugs are never a topic of conversation around the dinner table, others are influenced by their parents at young ages to try dangerous and harmful substances.

“[Parents] could save their kids’ lives by just talking about it once,” Smith said. “Or, they could save someone else’s life by teaching their kids not to judge drug addicts.”